Industry Talk

The publishing Industry in Search of a Second Life

by Warren Singh-Bartlett

September 7, 2016

Let’s begin with Scylla. As the lifeblood of any print publication, decreased advertising means less money for contributors and to fund the in-depth, unique stories vital to keeping readers coming back.

In recent years, one response has been for magazines to move online. With lower overheads and a wider audience, survival should be possible on less.

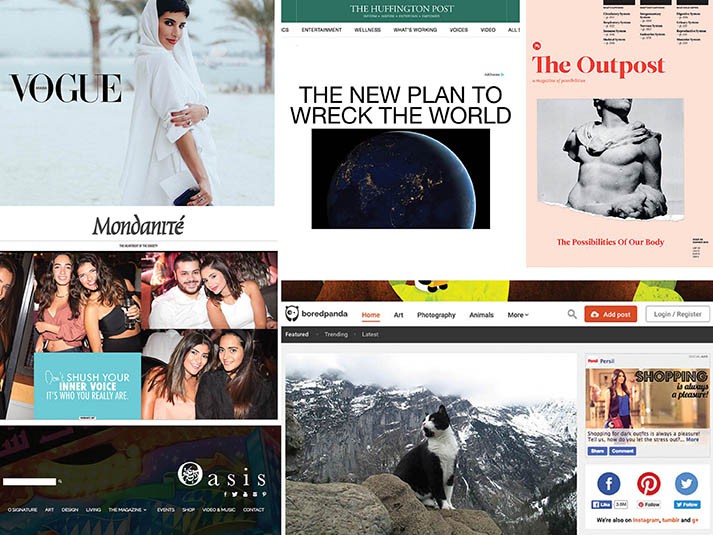

While some magazines do thrive online - Newsweek saw its fortunes rise after it abandoned print in 2012 - the most successful are digital versions of magazines that have already built their reputations in the real world. Thus Vogue Arabia, which launches this September in Dubai in partnership with Shashi Menon’s online publishing house, Nervora, is able to make its debut exclusively online because, well, it is Vogue.

While some magazines do thrive online - Newsweek saw its fortunes rise after it abandoned print in 2012 - the most successful are digital versions of magazines that have already built their reputations in the real world. Thus Vogue Arabia, which launches this September in Dubai in partnership with Shashi Menon’s online publishing house, Nervora, is able to make its debut exclusively online because, well, it is Vogue.

Now for Charybdis. Online advertising revenues are insignificant until a site has hundreds of thousands of unique visitors every day. If you are a brand new publication or a small existing one, the only way to get that kind of traffic is to invest time and money. And if you don’t have advertising revenues, well, you see where I am going.

In an effort to stay solvent, many magazines squeeze contributors. Pay rates have dropped and in some cases disappeared – that titan of online publishing, the Huffington Post rarely pays, considering publication reward enough – and there has been an exodus of writers and photographers in search of better-paid work elsewhere.

Things are not not as bleak as they might seem. A massive transition is underway and while there is still no clear sense of where this will lead, signs suggest that if traditional publishing, with its focus on making money from a single product, may be dead, the publishing industry itself may be entering a second life.

Print remains, as the French say, ‘incontournable’. It’s not just that there has been an explosion of independent magazines, enamoured to the point of fetish with print (and perversely powered by the generation that grew up with the Internet), it’s that even for mavericks like Vogue Arabia, a paper edition is already scheduled for early 2017 and for all the fanfare accompanying this ‘bold new experiment’, neither Condé Nast or Nervora appear prepared to bank on digital. Even more tellingly, two years after it famously migrated online, Newsweek returned to print in 2014. With a higher cover price and limited distribution, the print edition is aimed at a smaller, premium market. It survives on subscriptions, not advertising and began turning a profit within a year.

It isn’t just the behemoths that are adopting this digital-plus-premium paradigm. Frustrated by the lack of interest their quarterly arts and culture magazine received from advertisers in Saudi Arabia, unable to cut costs any further and unwilling to give up, Noura and Basma Bouzo decided to take their magazine, Oasis, in a different direction.

It isn’t just the behemoths that are adopting this digital-plus-premium paradigm. Frustrated by the lack of interest their quarterly arts and culture magazine received from advertisers in Saudi Arabia, unable to cut costs any further and unwilling to give up, Noura and Basma Bouzo decided to take their magazine, Oasis, in a different direction.

“Advertisers were looking for print runs in the 50,000 a week category, so they didn’t care about us. We got tired of chasing them,” Basma explained by phone. “It took too much of our time and we felt that the game was rigged in the Gulf. The agencies have the same clients and all work together.”

After a hiatus of almost a year, the sisters relaunch Oasis this October. The magazine will become a biannual, limited edition print aimed at collectors and print lovers and will be priced substantially higher. More regular articles will appear on a new website, which will be given over each month to a different curator.

“It will be a totally different beast to the print edition,” Basma continues. “Things we can’t publish in the magazine will go online. We see the digital edition as a kind of ‘thank you’ to existing readers and a way to attract a new readership to the print magazine.”

To cover costs, the sisters are shifting away from advertising and into work they get through Oasis; curating and event management and planning. They’re also about to launch their own Saudi lifestyle brand, traditional, handcrafted products with a contemporary twist, which may later be marketed through the digital magazine.

It is a route with which The Outpost is also familiar. A Beirut-based biannual publication in its fourth year, and self-styled magazine of the possible, it now sells more copies in Europe than at home.

It is a route with which The Outpost is also familiar. A Beirut-based biannual publication in its fourth year, and self-styled magazine of the possible, it now sells more copies in Europe than at home.

Their focus, however, is reversed. The Outpost is solidly print. It operates a basic placeholder site that directs visitors to an online store to purchase the print edition and its social media presence, which editor Ibrahim Nehme calls “friendly”, is more a series of status updates on the progress of the print edition.

“When first started, we were so focussed on developing our print product that we did not have enough resources left for online,” Nehme explains. “We're a very small team and we just didn’t have the means to pull off something decent online as well. It's not about not wanting to do something online but I don't want to do something that won't cover its costs and I still don't know what is it I can do online that would.”

The Outpost stopped looking for advertising after its fifth edition and secures much of its funding from magazine sales and sales of peripheral goods available at the launch parties held for each new issue. At $13 an issue, The Outpost isn’t cheap but Nehme says that readers appreciate the magazine’s take on the region as well as the effort that goes into creating each edition and so are willing to pay for a premium product.

It’s no stranger to finding alternate sources of revenue and funded its second year through a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo and it also applies for grants but it is side ventures in book publishing and consultancy that enable it to make ends meet. Money remains tight and Nehme admits to feeling frustrated that The Outpost is not always in a position to pay contributors.

About to take a break to reflect on how to maintain independence and raise more funding, ideas being considered include organising events and conferences linked to the ideas explored in each themed issue of the magazine.

But even big publications that still play the advertising game are exploring other options. Ghassan Omeira, editor of Lebanese lifestyle magazine Mondanité says that adding to the problem of making ends meet, publications must now operate multiple platforms - digital, social media – simply to stay relevant.

But even big publications that still play the advertising game are exploring other options. Ghassan Omeira, editor of Lebanese lifestyle magazine Mondanité says that adding to the problem of making ends meet, publications must now operate multiple platforms - digital, social media – simply to stay relevant.

“We maintain Mondanité’s social media accounts daily. We use them as a teaser to promote an event or an article and then if you want to see the full story, you have to read the magazine,” he explains. “This is an extra cost for us. You need a specialist for each and every account. Will it be beneficial in the long-term? I don't know. But we cannot neglect social media.”

With no increase in advertising revenues to cover this outlay, like Oasis and The Outpost, Omeira has developed a business model that supplements traditional sources of print revenue to keep the social media arm afloat. In addition to its sister publications – there are Kuwaiti and Emirati editions of Mondanité – the group operates a publishing arm and makes money from product placement and endorsements. In addition, through sister company OMG, it gains revenue from outdoor advertising. Looking ahead, Omeira is sanguine.

“What we offer through our online presence and social media accounts is a bundle for the advertisers to help promote their brands. Social media is an instant message and gets and instant reaction from the audience but it doesn't create awareness. The next day, readers don't remember ads they saw online,” he continues. “But with print, and we have this feedback from all our advertisers, many readers tear out the page and go directly to the shop asking for the product in the ad. That’s why luxury brands are still heavily present in print editions.”

While independence hasn’t allowed Oasis or The Outpost to do more than break even, at least for the moment, it does show that for smaller publishers and in Newsweek’s case, some much larger ones, survival is possible without the advertising industry. This may not yet provide comfort for writers, it does at least mean that their skills remain in demand and with universal agreement that content is king, a revival in fortunes may lie ahead.

For the advertising industry, though, things may be less appetising. Should more large magazines, all battling the downturn in revenues, decide to follow similar routes, it may one day be that in place of print being threatened by a lack of advertising, the advertising industry may be threatened by a lack of print magazines needing them. As Alanis Morissette once sang, wouldn’t that be ironic?