News - News In Brief

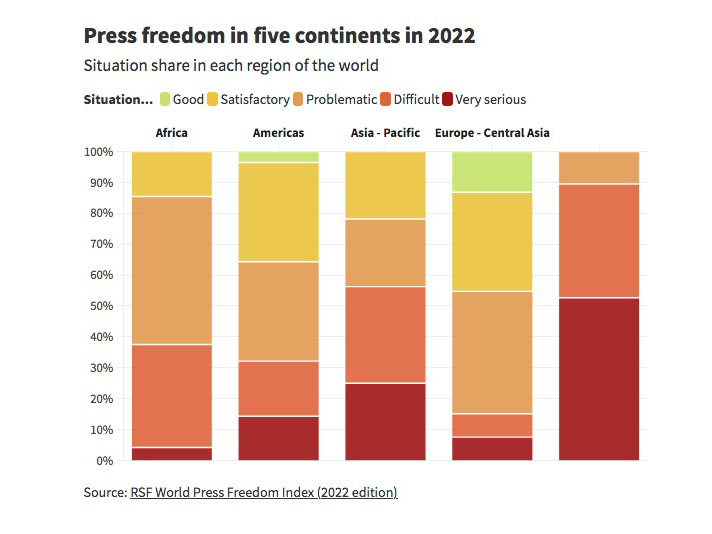

Generalized decline in MENA region according to RSF’s 2022 World Press Freedom Index

May 5, 2022

The 2022 edition of the World Press Freedom Index, which assesses the state of journalism in 180 countries and territories, highlights the disastrous effects of news and information chaos – the effects of a globalised and unregulated online information space that encourages fake news and propaganda.

Within democratic societies, divisions are growing as a result of the spread of opinion media following the “Fox News model” and the spread of disinformation circuits that are amplified by the way social media functions. At the international level, democracies are being weakened by the asymmetry between open societies and despotic regimes that control their media and online platforms while waging propaganda wars against democracies. Polarisation on these two levels is fuelling increased tension.

The invasion of Ukraine (106th) by Russia (155th) at the end of February reflects this process, as the physical conflict was preceded by a propaganda war. China (175th), one of the world’s most repressive autocratic regimes, uses its legislative arsenal to confine its population and cut it off from the rest of the world, especially the population of Hong Kong (148th), which has plummeted in the Index. Confrontation between “blocs” is growing, as seen between nationalist Narendra Modi’s India (150th) and Pakistan (157th). The lack of press freedom in the Middle East continues to impact the conflict between Israel (86th), Palestine (170th) and the Arab states.

Media polarisation is feeding and reinforcing internal social divisions in democratic societies such as the United States (42nd), despite president Joe Biden’s election. The increase in social and political tension is being fuelled by social media and new opinion media, especially in France (26th). The suppression of independent media is contributing to a sharp polarisation in “illiberal democracies” such as Poland (66th), where the authorities have consolidated their control over public broadcasting and their strategy of “re-Polonising” the privately-owned media.

The trio of Nordic countries at the top of the Index – Norway, Denmark and Sweden – continues to serve as a democratic model where freedom of expression flourishes, while Moldova (40th) and Bulgaria (91st) stand out this year thanks to a government change and the hope it has brought for improvement in the situation for journalists even if oligarchs still own or control the media.

The situation is classified as “very bad” in a record number of 28 countries in this year’s Index, while 12 countries, including Belarus (153rd) and Russia (155th), are on the Index’s red list (indicating “very bad” press freedom situations) on the map. The world’s 10 worst countries for press freedom include Myanmar (176th), where the February 2021 coup d’état set press freedom back by 10 years, as well as China, Turkmenistan (177th), Iran (178th), Eritrea (179th) and North Korea (180th).

RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire said: “Margarita Simonyan, the Editor in Chief of RT (the former Russia Today), revealed what she really thinks in a Russia One TV broadcast when she said, ‘no great nation can exist without control over information.’ The creation of media weaponry in authoritarian countries eliminates their citizens’ right to information but is also linked to the rise in international tension, which can lead to the worst kind of wars. Domestically, the ‘Fox News-isation’ of the media poses a fatal danger for democracies because it undermines the basis of civil harmony and tolerant public debate. Urgent decisions are needed in response to these issues, promoting a New Deal for Journalism, as proposed by the Forum on Information and Democracy, and adopting an appropriate legal framework, with a system to protect democratic online information spaces.”

Middle East - North Africa: Generalized decline and deadly East

The situation for the press in North Africa (excluding Egypt) has never been so troubling. Four countries present especially alarming conditions: Algeria (134th), where press freedom is drastically declining and the imprisonment of journalists is becoming routine; Morocco (135th) which is keeping three leading journalists in prison despite pressure to release them; and finally Libya (143rd) and Sudan (151st), where observers and our correspondents report that the free press has disappeared. In Algeria, the situation seriously deteriorated in 2021: many journalists have been imprisoned, prosecuted, or barred from traveling. As of late April, three of them were still behind bars. In addition, news sites have been blocked, and some publications critical of the government have been financially strangled.

In Morocco, press freedom has declined significantly, and few independent media outlets remain in operation. Three major criminal cases involving Taoufik Bouachrine in May 2018, and Omar Radi and Souleiman Raissouni in May 2020, who were arrested, prosecuted, and detained on spurious grounds, have increased pressure on the media. The situation is even more dire in Libya and Sudan, where the absence of a genuine government prevents the establishment of press freedom and acceptable working conditions for reporters. In addition, there have been attempts to control broadcast media outlets, and the military is omnipresent, especially in Sudan.

The situation is somewhat less worrisome in Mauritania (97th). There, a democratic interlude from 2005 to 2008 saw the de-criminalisation of press offences and a weakening of the repressive legal framework. Despite the government’s assertion that it favours peaceful dialogue with the opposition, journalists find themselves in extremely precarious situations that encourage collusion, bias, and self-censorship. And in Tunisia (94th), freedom of the press and information are undeniable achievements of the new constitution, adopted in 2014. But serious concerns have arisen following the July 25 2021 power grab by President Kais Saied, who decreed a state of emergency.

Journalists risking their lives in the Middle East

There is still a long way to go before the Middle East becomes safe for journalists. In 2021, several were killed while working or deliberately murdered. In Lebanon (130th), journalist and political analyst Lokman Slim was found dead near his car. As a tough critic of Hezbollah, he knew there was a bounty on his head.

Lebanon is in danger of sinking into a spiral of violence; online attacks and death threats against journalists are on the rise, and sometimes the threats become reality. Official inaction has forced many journalists into exile. The city of Aden, Yemen (169th) rivals Lebanon as a high-risk place for reporters. Three succumbed to their injuries sustained in explosions while on the job, and another, Mahmoud Alotmei, survived an assassination attempt by car bomb. But his wife Rasha Abdallah Alharazy, also a journalist, was with him and was killed.

As for Palestinian journalists, they once again paid a heavy price during conflicts in Jerusalem in May 2021 and again during the Israeli military offensive in the Gaza Strip (170th), where two journalists were killed in bombings. Elsewhere in the region, Saudi Arabia (166th), which just succeeded in having Turkey (149th) transfer the Jamal Khashoggi case for trial in the kingdom’s courts, is one of the world’s worst prisons for journalists.

In Iran (178th) 2021 was another tough year for press freedom. The two main leaders accused of abuses and crimes committed against journalists for 30 years, Ebrahim Raisi and Gholam Hossein Mohseni-Ejei, became, respectively, president of the republic and head of the Iranian judicial system. The result: an increase in arbitrary arrests and convictions, and journalists imprisoned and denied medical care.

New way of compiling the Index

Working with a committee of seven experts from the academic and media sectors, RSF developed a new methodology to compile the 20th World Press Freedom Index.

The new methodology defines press freedom as “the effective possibility for journalists, as individuals and as groups, to select, produce and disseminate news and information in the public interest, independently from political, economic, legal and social interference, and without threats to their physical and mental safety.” In order to reflect press freedom’s complexity, five new indicators are now used to compile the Index: the political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context, and security.

In the 180 countries and territories ranked by RSF, indicators are assessed on the basis of a quantitative survey of press freedom violations and abuses against journalists and media, and a qualitative study based on the responses of hundreds of press freedom experts selected by RSF (journalists, academics and human rights defenders) to a questionnaire with 123 questions. The questionnaire has been updated to take better account of new challenges, including those linked to media digitalisation.

In light of this new methodology, care should be taken when comparing the 2022 rankings and scores with those from 2021. Data-gathering for this year’s Index stopped at the end of January 2022, but updates for January to March 2022 were carried out for countries where the situation had changed dramatically (Russia, Ukraine and Mali).