News In Brief

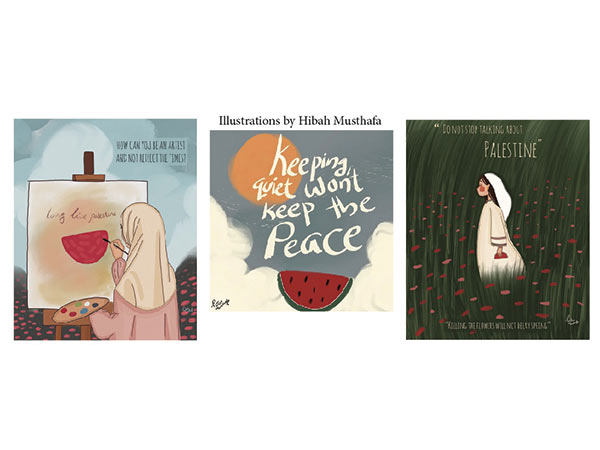

Gaza War: why has the ad industry suddenly lost its voice

Iain Akerman

6-September-2024

In the wake of the 7 October attack, in which an estimated 1,200 Israelis were killed by Hamas and Islamic Jihad militants, agency bosses expressed their solidarity with Israel. Arthur Sadoun, the chief executive of Publicis Groupe, told staff in Israel that the group would “unequivocally stand by you in these tragic and trying times”. Yannick Bolloré, Havas’ chief executive, wrote of his deepest thoughts being “with our more than 100 Havas colleagues on the ground and their loved ones”. Bolloré even acknowledged Israel’s declaration of war, which meant that “some of our collaborators will be called to duty”.

Not a single word has since been uttered in defence of Gaza, despite the killing of more than 40,000 Palestinians at the time of writing. No calls for a ceasefire have been forthcoming.

For an industry that prides itself on driving positive change and campaigning for good, the advertising world has remained shockingly silent on Gaza. Why?

Why have brands and their agencies, both of which have been quick to speak out on socio-political issues in the past, remained silent in the face of Israel’s assault on Gaza? A silence that not only permeates the higher echelons of adland’s holding groups, but individual agencies and their employees.

“Fear is the most logical explanation,” says Amir, who, given the potential repercussions, wishes to remain anonymous. “Fear of reprisal, fear of reputational damage, fear of the loss of your job and livelihood. Just fear.”

This fear is justified. In the US, pro-Palestinian voices have been cancelled, including that of David Velasco, the editor of Artforum, who was fired for signing an open letter that called for “Palestinian liberation and… an end to the killing and harming of all civilians”.

In April, Google fired 50 employees for protesting against the company’s participation in Project Nimbus, which involves the supplying of artificial intelligence and cloud computing services to the Israeli military.

Meanwhile, students across the US have been beaten and arrested in their thousands.

“There’s a legitimate fear surrounding speaking out, especially when livelihoods are on the line,” says Aaliyah, who also wishes to remain anonymous. “However, what’s even more daunting is the prospect of living with the regret of staying silent in the face of injustice.

At the core of it all is a question of humanity – whether we choose to turn a blind eye or raise our voices. It’s a matter of conscience and courage, knowing that silence only perpetuates suffering while speaking out holds the potential to ignite change and uphold basic principles of justice and human rights. So yes, the fear is there, but the moral imperative to stand up for what’s right outweighs it in my opinion. The loss of lives is and should be greater than any financial, academic and professional loss.”

For those in the region’s advertising industry who have spoken out, the repercussions have been varied. Individuals and agencies have been blacklisted, while others have been threatened with disciplinary action. Voices have been silenced, especially on professional platforms such as LinkedIn, and any discussion of Gaza is being suppressed.

“Personally, I’ve been told to set aside my ‘emotions’ and focus on my work, or consider leaving,” says Aaliyah. “With a silent warning about the consequences of my ‘emotional outbursts’, making it noted that continuing to be outspoken, opinionated, and stubborn will make for a rather difficult personal and/or professional journey in the future.”

Who is driving this silence? Agencies themselves? Brands? Holding groups? “It’s a collective responsibility,” replies Aaliyah. “From line managers to corporations, from governments to social circles, the pressure to remain silent seeps through many levels of society. But when lives are at stake – when 34,000 have died and millions are displaced and cities have burned to the ground – the fear of losing a job or facing social repercussions pales in comparison. We’ve reached a point where risking it all is not just about personal sacrifice but about standing up for the fundamental principles of humanity.”

There are also vested interests. All holding groups have agencies operating in Israel (Publicis Groupe, for example, has over 400 staff in Tel Aviv) and Israel has an effective stranglehold on big tech.

Various agencies work for lobbying groups such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which is set to spend $100 million on political campaigns in the run-up to the US elections. Much of that money will be spent on targeting members of Congress critical of Israel.

Last November, the Democratic Majority for Israel rolled out a targeted advertising campaign that undermined US politicians critical of Israel’s war against Hamas. The campaign included ads against Rashida Tlaib, the only Palestinian-American in Congress, accusing her of being on the “wrong side of history and humanity”.

“There’s the risk of losing business, money, and reputation, not to mention facing threats,” says Aaliyah. “Even judges at the International Court of Justice are receiving death threats. So, can we honestly say that big corporations, already deeply entwined with Israel and with millions at stake, would have the balls to risk it all? It’s rhetorical at this point.”

“I find this whole debate on pulling the brand world into political debates to be pure exploitation for profit – from any angle whatsoever.”

--Asad ur Rehman, CEO So&So Partnerships.

For the wider industry, the overriding stance is one of non-engagement.

Taking sides in a political conflict does not lie within the remit of companies, say agencies, irrespective of the severity of the humanitarian disaster in Gaza.

Industry leaders are therefore content to sit quietly on the sidelines, hoping nobody calls them out for failing to condemn the killing of over 34,000 Palestinians. These leaders have ensured the silence of their staff, threatening those who speak out with disciplinary action and refusing to engage with the media industry. None of the multinational agencies contacted for this article agreed to participate.

To the emotionally disengaged, or to fans of the American economist and statistician Milton Friedman, such a stance is understandable. Friedman believed that the primary responsibility of a corporation was to maximise profits for its shareholders, not to engage in political or social dialogue. Those who believe in such a doctrine point to the dangers of becoming involved in international affairs, including reputational damage, consumer fallout, economic retaliation, falling sales, and employee discontent.

“I find this whole debate on pulling the brand world into political debates to be pure exploitation for profit – from any angle whatsoever,” says Asad ur Rehman, chief executive of So&So Partnerships. “Whether done for the victim, or for the oppressor. Brands create communication with one – and only one – objective: to sell more in the short or long term. With that, any use of any political situation in any campaigns has questionable belief systems behind it.” That includes fashion and skincare brands who have exploited the watermelon and the Palestinian keffiyeh for profit, some of whom claim to send money to Gaza, says Rehman.

However, inaction is also destructive. You only have to look at Google – where employees have faced hostility, recrimination, and the loss of their livelihoods for standing in solidarity with Palestine – to realise that companies that have supported Israel or censured, silenced, or fired their employees are at risk of long-term reputational damage. The same applies to agencies and their clients, who face the additional slur of somehow losing their moral voice when it is most needed.

“Advertising and marketing agencies are not merely selling products, they’re meant to be shaping narratives, influencing opinions, and reflecting the world around us,” believes Aaliyah. “Transparency and relevance are vital in our line of work. Ignoring political and social issues is not only tone-deaf but also comes across as indifference to audiences. We need to be sensitive to the realities people face and the current state of the world. It’s not about taking sides (even though it’s blindingly clear); it’s about being conscientious and understanding the pulse of society. In short, we can’t afford to be politically or socially disengaged – we need to read the room and respond accordingly.”